Envision yourself as a new hemodialysis patient. You are asked to arrive at the dialysis clinic before the sun even begins to rise. You arrive with little sleep and are called into the unit, escorted to a chair that seems to be on the outer reaches of the universe, and are expected to spend the next four to five hours of your life there, every other day.

Not only are you tired, you are numb and unsure of what is expected of you. You are afraid of what the day will bring—possibly fluid overload and not feeling well physically.

A nurse approaches you carrying what appears to be an unending pile of forms. He/she sits down next to you and asks you to begin signing the consents that places your life in their hands.

You have had to start dialysis without delay—having had a dialysis catheter placed just days ago. The nurse/technician connects you to the dialysis machine, and you are in disbelief about what is happening to you. You see your blood being taken from your body and sent to a machine to be “cleaned.” All around you are new sights and deafening sounds that burden your senses. Some way or another you manage to complete your dialysis session and before you know it, several weeks have gone by and you are being sent back to the hospital to have an arteriovenous (AV) fistula/graft placed.

Yet another strain on your daily life. However, you have the nurses and technicians telling you that this is the “best way to go.” You are introduced to the dietitian, social worker, vascular access nurse, nephrologist—with everyone imparting more advice and information—with you becoming more and more overwhelmed.

Look at what the social worker has to do, initial admission notes, initial care plan, initial psychosocial assessment, and progress notes care plan.1

As the weeks go by you start to become more accustomed to your dialysis treatment regimen, learning more about your disease process, and focusing on how to develop, protect, and preserve your fistula/graft.

Before you know it, the day arrives for your first cannulation. The dialysis staff approaches you and imparts the most feared word in dialysis, “I’m here to stick you today.” As health professionals, the correct terminology should be, “I’m here to cannulate you today.”

This author would like to propose an alternative way to help new patients transition to their life on dialysis. New patients could be brought into the clinic on a second shift.

Between 10 a.m. and 11 a.m., Monday, Wednesday, and Friday they can be scheduled to dialyze in chairs dedicated specifically for new patients. Two to six chairs would be centrally located near the nurses’ station allowing for constant visualization and supervision.

The dietitian, social worker, vascular access nurse and nephrologist would have easy access to the new patients, and the information and education provided would be repeated allowing the patient time to assimilate and incorporate into their life on dialysis.

Having a centralized location for the new patients also allows them the opportunity to talk amongst themselves regarding their experiences and build rapport and a stronger support system within the dialysis unit. It is important to note that patients be informed from the beginning that this seating arrangement is only temporary and will be for approximately three to four months, at which time they would transition to the main unit, allowing for newly admitted patients to take their spot.

Having worked, visited, and given advice in cannulation techniques in 86 clinics over the past 15 years, this author has also come to the conclusion that a way to improve the outcomes of fistula survival is through continuity of care, utilizing the dialysis unit’s expert cannulators to begin cannulation and development of the fistula.

It is essential that the cannulator work a regular schedule for a designated period of time (e.g. six months), and then rotate out with another expert cannulator. This can be a very difficult decision for the nurse manager to make, as it may cause jealousy or additional tension among staff. However, your patients are counting on having a fistula that can be developed and utilized without difficulty.

A tier 1 cannulator is one that has shown a high degree of cannulation success and has at least two years experience. There are exceptions to this in that there are nurses and technicians that exhibit “natural” talent and technique who become expert cannulators prior to the two-year experience. I have noted that approximately one out of every seven new staff working in dialysis exhibit this ability, and some have even advanced to a tier 1 cannulator within a minimum of six months experience.

The tier 3 cannulators are new staff members or those who consistently have cannulation difficulties such as infiltrations. The Fistula First program has a check list for determining cannulation skills that can be utilized as a resource to determine each staff member’s abilities and areas for improvement

“Sample Dialysis Facility Guidelines for Rating and Improving Staff Cannulation Competency” Revised 09/09 Fistula first Section 8. It is recommended that staff be required to utilize the “cushion cannulation” technique2 and if buttonhole access is involved the “touch cannulation technique”3 should be used.

Empowering our patients to become familiar with and learn more about their disease process and their access is of great importance.

Encouraging the patient who is able to self-cannulate cannot only help the patient have control over their treatment, but they are more likely to have better compliance with issues such as fluid intake, dietary restrictions, KT/v, etc.

The patient has been able to observe staff in preparing other patients for self-cannulation and has a sense of what to expect. Approximately two weeks prior to cannulation you can begin having the patient wash and prep their arm following unit policy. Using a buttonhole needle with the needle guard in place two cannulation techniques are taught: the rope ladder and buttonhole.

A needle guard cap can be cut in half and used to help explain how the needle track is very similar to the buttonhole tunnel by slipping a buttonhole needle into the guard. The patient should be taught how to pick up the needle and place the palm of their hand on their arm.

Using their thumb and forefinger they cock the needle and push forward using “touch cannulation.” Approximately one week before cannulation is initiated, the patient repeats this process; however, this time the needle guard is taken off and “Tandem Hand” cannulation is started. This procedure is to get the patients involved and feel what is to take place the actual day of cannulation.

Experience has also revealed to me that many patients have difficulty visualizing the cannulation site and it has been of benefit to evaluate the patient’s eyesight prior to their first cannulation attempt. Taking a fine point sharpie, place a small dot on the fistula to see if the patient is able to line up the tip of the needle with the dot. Many times the patients cannot do this (~40 percent in practice experience) and it can be remedied simply by providing an inexpensive pair of reading glasses. The unit can keep a small assortment of various magnifications for the patient to try and then provide them with a pair for their use. Once that problem is out of the way, we can begin to fine tune the process.

The week of cannulation, the needle guard is taken off the buttonhole needle and the patient is taught touch cannulation putting pressure on the intended track of the access.

The patient is encouraged to do this 10 to 12 times, which sends a small amount of pain to the brain and allows it to become accustomed to the pain. Repetitive painful stimulation is known to produce a decrease in a patient’s perception of pain over time.

This process, called pain habituation was extensively investigated.5,6 In a recent article5 20 subjects received a series of 10 blocks of six 6s thermode stimuli. After each block, they were asked to rate their pain on a scale of zero to 100. The researchers found that the mean pain ratings decreased gradually over eight days. Most importantly, there was a significant difference in pain perception from day one to day eight which shows that with repetition, painful stimuli will hurt less.

During the first few cannulation attempts the patient should be informed that there will be pain associated with the cannulation, however the more cannulation that is performed the less pain they will experience using the buttonhole technique.

There are reports that some patients continue to experience pain and it is recommended that a new buttonhole site be established should this occur. It is rare for a patient to be in pain all the time, however it does happen. Should this occur, lidocaine and other pain control measures can be evaluated and trialed but this is rare.

You’ve now arrived at the day of cannulation, where your patient has received the information and education regarding what to expect and what is expected of them. Their fear has hopefully been lessened and they feel empowered and able to pursue self-cannulation. It is recommended that all patients who have the ability use the tandem hand cannulation technique while learning to cannulate. Once their confidence and skills have developed and the graft and/or buttonholes have been established, the patient can then make the decision of whether or not they wish to continue self-cannulation or have dialysis staff perform cannulation.

Some patients experience difficulty with their grafts moving or rolling when they cannulate. A technique that can be utilized to minimize this movement is to have the patient squeeze a ball as the needle is inserted. This help stabilize the graft/vessel in place for easier cannulation.

Three months have passed and the patient is ready to transition to the main unit. They have established a solid working relationship with their health care team, as well as developing a support system of patients experiencing the same things they are going through. Staff have also had time to get to know the patient and helped in developing the access and cannulation techniques that work best for their individual grafts/access.

Instead of the revolving door of get them in and get them out, staff has established a relationship of trust while attending to the information and education that every patient should have when beginning dialysis, in the hopes of decreasing treatment issues and access problems such as frequent infiltrations in the future.

There is a climate of change in the environment regarding cannulation and training of new patients as well as staff. The methods described above can help improve clinical outcomes and provide a more collaborative approach to patient care in powering the patient to a better life.

Tier 2 cannulators are staff members that have shown their skill in cannulation and have at least one year of cannulation experience. Tier 2 cannulators act as support and back up to the tier 1 cannulator after the patient has been in the unit for three months and is rotating out of the new patient seating and into the main dialysis clinical area.

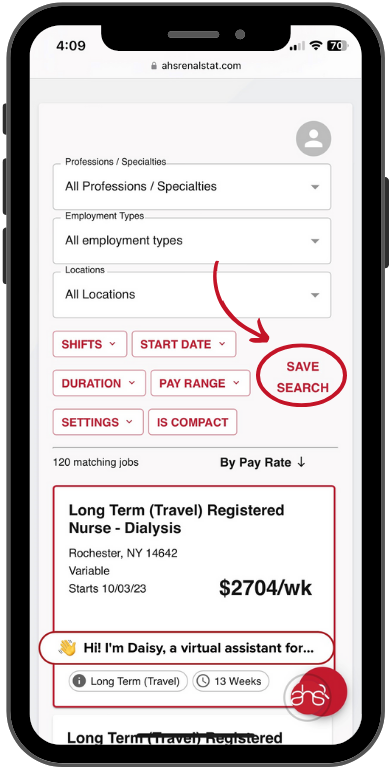

For entire article and references, go to RenalBusinessToday.com